Creative Movement

In the underdeveloped and somewhat hidden modern field of Meditative Art, it seems as though dance and creative movement has been one of the most popular art forms.

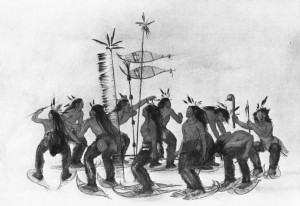

Searching history, we find interesting examples of Meditative dances and movements such as Sufi whirling, tribal dances and classic Indian dances.

Even flowing styles of Chi Kong and yoga can be seen as forms of creative movement. While these modern styles of traditional practice bring a fresh flow and openness, they still make use of the essence of their past wisdom and depth.

In the last century, well known spiritual teachers, such as Gurdjieff and Osho, created dances as a tool to help personal development. The focus of many of these kinds of dances has never been on one’s spiritual evolution in the sense of connecting, surrendering and merging into that which is divine, but rather growing and developing on a more personal level. At times, unfortunately, these and similar kinds of dances are used for escapism – to lose ourselves and “disappear”. As suffering human beings, we all have the wish of just “going away”, of avoiding life’s pain and suffering. But, using these practices in such a way is not much different, in essence, from taking drugs or from getting drunk.

In truth, what art “wishes” to be used as, is as a form of worship, a prayer and a meditation; this worship is of our true self and of the divine.

Art is a gift we humans have received, so that we can express true feeling; such as love, gratitude, joy, deep longing, and even real pain and sadness.

Misunderstanding art may result in distorted and unhealthy expression, reflecting mental imbalances or general darkness.

Intention

When we come to perform a meditative practice of movement, our intention has a direct effect on our results. Our intention can be to “use” the practice for our selfish desire, in the hope to ‘get away’ from our problem, to find temporary relief from our habitual thinking and overly developed mind. This kind of practice can result in a so-called ‘ecstatic rage’ or ‘unconscious state’ – which may seem very spiritual, but in fact has nothing to do with spirituality.

If we come with the intention of using our body and movement as a way to connect to that which is within, combining a moderate level of awareness with much relaxation, openness, and humility, the practice has a completely different ‘fragrance’; a much more mature and calm energy that is in tune with the flow of creativity. We can then BE art.

Using art as a tool for inner growth must be done with respect – respect for ourselves and respect for art. When we have respect for something, we listen to its needs rather than trying to find ways to use it to serve our lower nature. When we have respect for ourselves, we don’t try to run away to some “lala land”, we actually look for ways to meet and to spend quality time with ourselves.

When we have respect for art, we don’t try to negate its meaningfulness with sallow and meaningless ways of thought, such as “everything is art” or “all art is spiritual”, but rather, we continuously seek depth and understanding of what art as and how it can be applied in a conscious and real manner.