Calligraphy

Meditative Art from the Far East

“Ancient ‘Mother India’ and ‘Father China’ of the Far East are both captivating in many ways; this includes the fields of Meditative Art forms. Both these profound cultures are of deep magical wisdom, which has amazingly survived through time.

While there are enough fascinating Meditative Art forms developed and practiced in these cultures to fill books and books, only a few had to be selected here. Sharing only a glimpse of these great cultures, it is made with the intention of capturing an inspiring essence. Perhaps these will be an incentive for the reader to explore more, theoretically and through personal experience.

…

Text from our book:

Meditative Art – Theory & Practice

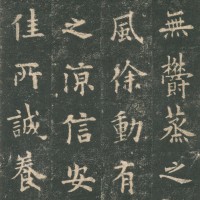

(Top Image : Chinese Calligraphy of regular script style from 632, a page of a Song Dynasty stone rubbing by Ouyang Xun 557-641)

Chinese Calligraphy

The term for the traditional Meditative Art practice in Chinese Calligraphy literally means “The Way, Method or Law”, in relation to discipline as well as to art.

Chinese Calligraphy, as well as Chinese traditional paintings, emphasize on a dynamic motion performed in a clear meditative inner state.

The Chinese script, known as Oracle Bone Script or Jai Gu Wen, is believed to have started 5000 years ago, as pictographic writing that was evidently expressed on bone and turtle shells. It is used for Shamanistic spiritual rituals. The Chinese script had developed and progressed through time, and was influenced by the different, important Chinese dynasties. Some of the ancient script writings are still used today.

(Side image: Taohe inkstone from Song Dynasty, China, with Ming Dynasty inscription (1368–1644). Nantoyōsō Collection, Japan)

Shū-fu calligraphy is a practice performed by monks and other spiritual or religious practitioners. Originally, the writings were used as a way to record spiritual wisdom, as well as a defined Meditative Art practice of writing poetry, and expressing visual art. The soft, flexible hairs of the brush, the carbon in the ink and the spontaneity of the movement of the character (letter) portrayed, is regarded as the essence or spirit of the Calligraphic art.

Shū-fu requires fine concentration, focus, correct physical posture, deep inner silence and much practice. Patience and precision, as well as firm discipline, are needed, and these qualities are also developed through repetitive and dedicated practice.

(Side image: Daruma by Hakuin Ekaku 1685 – 1768, scroll calligraphy depicts the Bodhidharma. Caption: Jikishin ninshin, Kensho jobutsu: “Direct pointing at the mind of man, seeing one’s nature and becoming Buddha.” Exhibit in the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA)

Supportive & Creative Spiritual Tool

As all Meditative Arts, here, too, the practice is not a means for any result or product, rather as a supportive creative aid for spiritual search; one that unites the way with the goal. In ancient China, there was a belief that Calligraphy is a Divine gift, given by the Gods to mankind, as a wonderful tool to connect with divinity and its aspects.

Practitioners, observing their own Calligraphy work, are described as though looking at themselves in a mirror; this observation must be clean from judgment and constructive, as one must learn to see one’s present inner state in order to transform and evolve. This tool of reflecting on one’s own artwork is also understood to be an integral and important part of the spiritual practice of the Calligraphy Meditative Artist.

While Calligraphy can be beautiful and highly aesthetic, “real” Calligraphy is not to please the eye, but to express a true meditative state.”

Read more on: Meditative Art – Theory & Practice